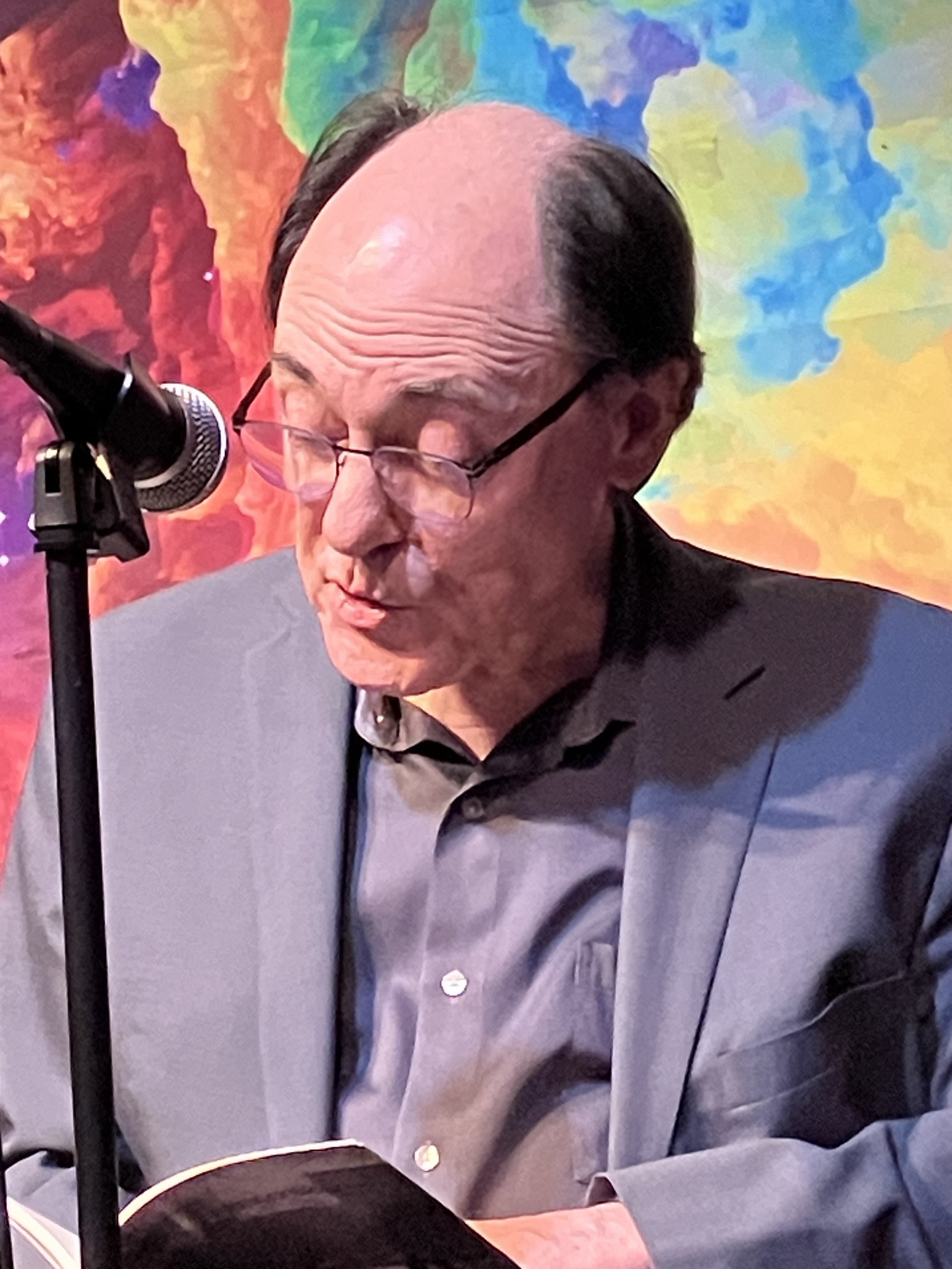

Geoffrey O'Brien: In the Pleasure Zone

Geoffrey O’Brien reading at Suite Bar in New York City, March 10, 2024. Photo by Linda Stern

Geoffrey O'Brien has written many books, including nine collections of poetry. Yet in Went Like It Came, his remarkable new collection, one of the poems is called "Goodbye to My Books."

That phrase and the clear act of leave-taking it implies are unmistakably reminiscent of Prospero, the arch magician in Shakespeare's The Tempest. In the play's final act, Prospero resolves to discard the tools of his magic and thus eliminate the spell over the shipwrecked visitors to the fantastical island that his sorcery has induced. "But this rough magic/I here abjure," Prospero declares:

I’ll break my staff,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I’ll drown my book.

Like Prospero, O'Brien calls forth the transformational magic implied by the drowning of arcane books of spells. In a nice phrase, O’Brien conjures "[m]etal bound magical grimoires" dredged up from the damp archives of a drowned city. Grim as it may sound, however, the deep-sixing (or full-fathom-fiving) of ancient spell books can yield a fresher, more dynamic sense of reality. "Nothing written down in a book/Is allowed to stand still" in this floating world where the ink smears, the eyes blur and, suddenly, as the poet writes:

The words are tiny people

Who barter objects in what seems like a marketplace

They yell at each other or exchange blows

The words become living beings in themselves, capable of harmonious exchange or cacophonous conflict. In this they resemble "Went Like It Came," the final cut on Village of the Pharoahs, the 1973 Pharoah Sanders jazz album from which O'Brien has taken his title. The tune ends the album as it began, with raucous percussion and Sanders's screeching tenor saxophone. Although O'Brien's distilled verse features clarity rather than roughness, his poetry and Sanders's sax runs gesture toward a timeless immediacy beyond technique. In one typically crystalizing phrase, the poet calls the aesthetic space that he and Sanders can be said to occupy "the zone of unending interlude."

The pleasure zone in which O'Brien's recent poems also may be said to float is film noir. This is to be expected from the author of such prose works as Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks And The Masters Of Noir and film reviews for the Criterion Collection of such classics as The Asphalt Jungle and The Killers. Further evidence is available in the poet's prior volume, Who Goes There, where we can find poems entitled "Neo-Noir," "Vertigo," and "Night Song."

But don't get the idea that O'Brien is dishing out Chandler or Goodis or Cain in verse. Instead, the poet boils down the varied elements of the crime novel into something like the genre’s Platonic form, creating the atmosphere and substrate on which some of his finest poems are built. For example, the superb and riveting 12-part sequence "A Story in Memory of John Ashbery," lays out the range of subject matter you might find in any given pulp:

it could have been the one

about the missing will or the missing person,

the blackmailed movie star, the body

in the locked room, the wronged convict

looking for payback from the man who sent him up

Entertaining as O'Brien's endeavor is, it's important to remember that he's writing lyric poetry of a high philosophical order, purifying Ashbery's metaphysics as much as he is culling the felicities of noir. Time is of the essence in both genres. In lines that could well be describing the designs of poetry on the reader, O'Brien writes:

…mysteries are designed

to make time pass as quickly and imperceptibly

as possible, to obliterate time and replace it

with what is experienced as endless and endlessly pleasurable